Now that the Royal Dividends portfolio has received its first dividend, it makes sense to address what we should do with them. Whenever you receive dividends from your various stock holdings, you have three options:

- Spend the dividends.

- Do nothing.

- Reinvest the dividends.

All three options have merit. For instance, dividends are often a significant source of income for retirees. Retirees may use their dividend income to pay bills or buy groceries. However, for those in the saving phase of their lives, spending dividends is to be avoided. Reinvesting is best and oddly enough, the best way to reinvest involves doing nothing – at least initially.

Let me explain.

Why You Should Reinvest

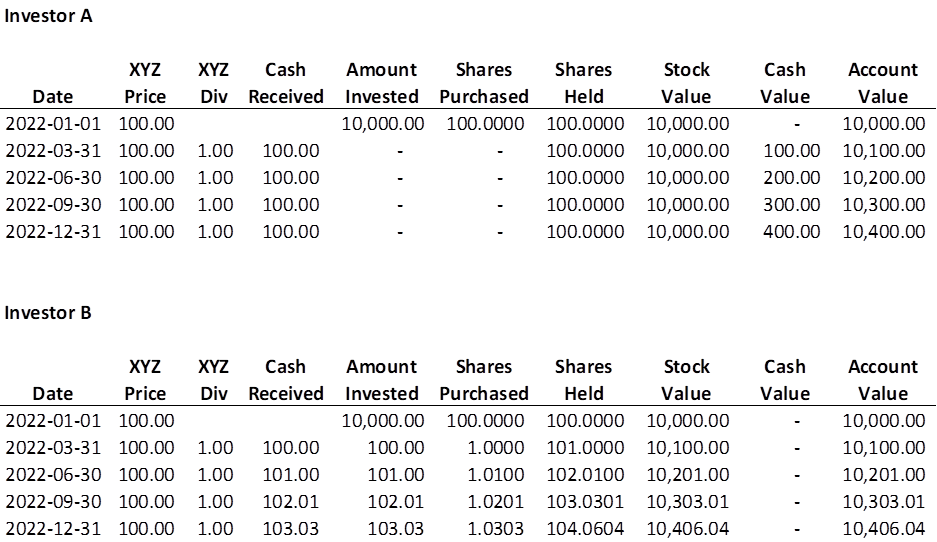

Reinvesting dividends allows the investor to compound their wealth. Compounding refers to the ability of a sum of money to grow exponentially over time. Suppose we have a stock, XYZ, that on January 1st, trades for $100. Further, XYZ expects to pay a quarterly dividend of $1 on March 31st, June 30th, September 30, and December 31st. Now, suppose we have two investors, Investor A and Investor B. Each invests $10,000 in XYZ stock and acquires 100 shares on January 1st. Investor A does nothing with the dividends that come in. Investor B chooses to automatically reinvest his dividends purchasing more XYZ stock each quarter.

One year later, XYZ is still trading for $100 and, as expected, has paid out $4 in dividends. Investor A now has 100 shares valued at $10,000 and $400 in cash for a total of $10,400.

We need to know the price at which Investor B purchased XYZ throughout the year. For simplicity, let’s assume that XYZ just happened to be trading at $100 on each of the days it paid its dividend. After one year, Investor B has 104.0604 shares valued at $10,406.04. That’s $6.04 more than Investor A. The table below shows why.

Because the dividend paid is based on the shares held at the time of the ex-dividend date which precedes the payment date, the new shares purchased on the same day do not contribute to the amount received. That is why the account values are still identical on March 31st. But from that day forward, the compounding begins. Note how Investor A’s account grows linearly, by $100 each quarter. By contrast, Investor B’s account grows by an increasing amount as each quarter passes. This is exponential growth due entirely to the reinvestment of the dividend payment towards the purchase of more shares each quarter.

Can Reinvesting Work Against You?

I chose the simplified example above, where the stock price remains unchanged throughout the year (or at least, just happens to be $100 at the end of each quarter – feel free to assume it fluctuated wildly on the other days), because it best isolates the impact of compounding. It is really quite similar to having money in a savings account that pays interest and never withdrawing from the account; the principal and interest each grow with interest. And no surprise, in those banking situations, we refer to the interest being credited to savings accounts as compound interest.

Holding stock, though, is just a bit more complex as there is the underlying value of the shares that complexifies matters. Investor B’s number of held shares is growing each quarter and the stock price never changes.

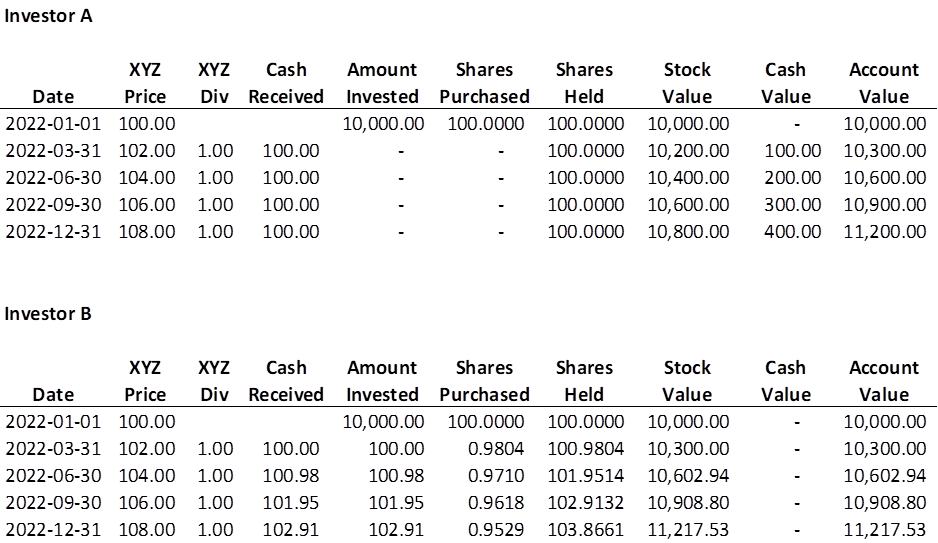

What if the stock had climbed steadily throughout the year?

Investor B now has $17.53 more than Investor A. He ended up purchasing a smaller fraction of shares each quarter, but the number of shares held kept growing. The value of the shares grew as well; the effect of compounding was compounded! Investor A’s cash did not grow. Of course, it is possible for any cash received to be swept into a money market account or similar vehicle that credits a small amount of interest, but I wanted to keep the example simple. No cash vehicle at your bank or brokerage is going to credit enough interest to overcome having missed out on the 8% annual growth of XYZ’s share price, let alone total return from reinvesting those dividends.

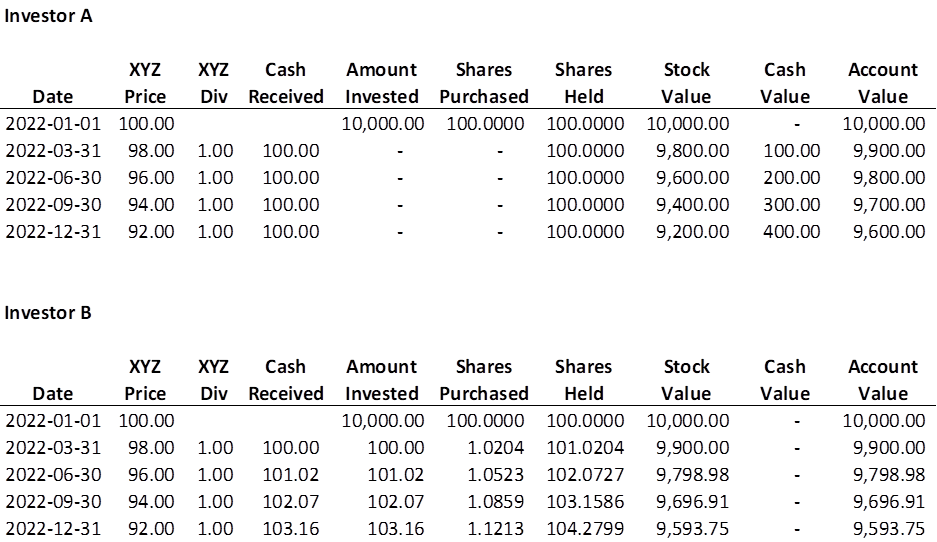

What if the stock had dropped steadily throughout the year?

Investor A has $6.25 more than Investor B. This should make sense. Keeping one’s dividends as cash which earns 0% is better than reinvesting in a stock that is losing 8% annually. Of course, if one knows in advance that a stock is going to drop, why buy it in the first place? We just can’t know for sure, so why not reinvest those dividends and average down on the acquisition price. Investor B has invested $10,000 of his own money and has 104.2799 shares at an average cost of just under $95.90, whereas Investor A’s cost is still $100 per share. If both investors still have the same conviction that XYZ is a good investment with upward potential, Investor B’s account will be back to square earlier than Investor A’s1.

Reinvesting Methods

Let’s assume that you’ve chosen to reinvest your dividends. It is the best decision in the aggregate, and over the long haul, as it virtually guarantees a compounding effect to your wealth. It is even a good idea for retirees not to withdraw and spend all of their dividends, but to reinvest even just a small percentage, to give their principal a chance to grow and produce more dividends.

An investor has essentially three options for reinvesting dividends.

- Enter a direct stock purchase plan (DSPP) with a dividend-paying company.

- Enter a dividend reinvestment plan (DRIP) program with your broker.

- Reinvest dividends into the stock with the highest expected total return.

DSPP

It is possible to enter a DSPP with a dividend-paying company directly. They’re not as popular as they used to be, because they don’t have the advantages over brokerage firms that they used to have. It used to be that a person who could not afford to buy a round lot (100 shares) of a stock would pay a rather large commission to acquire at least one share of the stock and have the stock certificate sent to them in the mail. It was not uncommon to pay a $35 flat fee to get the necessary 1 share registered under their name. The investor would then send the certificate directly to the company or to a holding company that administers the DSPP and open up an account. From there, the advantages were obvious. Most DSPPs allowed the investor to purchase whole or even fractional shares, with no commission and less often, with a discount of 5 or 10% off the prevailing market rate. And of course, any dividends received would automatically acquire more whole or fractions of shares, again, with no charge. DSPP investors would often have accounts with several different companies, otherwise diversification would not be possible.

Now, with paper certificates having all but disappeared and electronic registration in street name being nearly universal at brokerages, it is easier to enter and fund DSPPs electronically. However, brokerage firms no longer charge large commissions on even the smallest of stock purchases (and several have no commissions at all) and they offer their own, much more flexible DRIP (see below). Thus, opening a DSPP is less attractive and antiquated. Maybe if you’re a grandparent who doesn’t want to go through the rigamarole of opening up a trust account for a child, opening a DSPP account with a couple of big stock names isn’t a bad idea. But I still think the next two options are better.

DRIP

In the examples above, Investor B has chosen to automatically reinvest his dividends through his broker’s DRIP program. This is the easiest and most passive way to invest one’s dividends. It is a feature that can be turned on within any brokerage account and it can even be done on a stock-by-stock basis. If the automatic reinvestment of dividends is turned on for a stock, that stock’s dividends and only the dividends from that stock will go towards purchasing more shares of that stock, in whole shares or even in fractional amounts, whenever dividends are paid. The purchase is usually made, commission free, on the next trading day but could be as many as three days out.

This is the perfect option for an individual who wants to disengage from their account and essentially just check the balance every month or quarter. There is nothing wrong with this approach for the passive investor, but there are three inconveniences

- There is no control over the price at which the new shares are acquired.

- Fractional shares cannot be sold unless the entire position (all shares) is sold.

- Only dividends from the stock itself can be used to purchase more shares of said stock.

We can do better.

The Best Way

When the government spends money, they often do it indiscriminately and inefficiently, overfunding programs that don’t need it at the expense of worthy programs that could use more. A DRIP is better than this approach (what approach isn’t better?) because at least when a stock’s price is significantly up, the number of shares acquired in the next purchase will be less than usual. And if the stock price has dropped significantly, the number of shares to be purchased will be greater than usual, all other things being equal. Again, a better approach is available to the active investor.

Let’s avoid all three inconveniences of the DRIP election. Do nothing initially. Collect all the dividends coming in, from all of the stocks in the portfolio, and let them accumulate as cash within the account. Then when their amount (plus any added funds) is enough to acquire more shares of a stock, select the stock that could benefit the most from reinvestment. This would be the stock with the highest expected total return. Quite often, this is not one of the stocks that has been performing well, but one whose share price has been beaten up a bit.

Defining ‘highest expected total return’ is a topic for another post but suffice it to say that if you still have all the same conviction you had when you first acquired your stocks, the stock you should purchase with the totality of all your dividends, from all your stocks, is the stock whose price has dropped the most or grown the least. This is how you get the most bang for your buck. If you’re following along with the Royal Dividend portfolio, let me worry about picking the stock for reinvestment.

After years of reinvesting dividends in the stock positions most worthy of that reinvestment, subject to the constraint that we do not hold too much in any one stock or sector, we will see our wealth compound. It is a tailored, bespoke DRIP that with years of discipline produces real drip.

1If XYZ were to climb back to $95.90 before the next ex-dividend date, Investor B would have an account value of $10,000.44. Investor A’s account value would be $9,990. This effect is known as dollar cost averaging and is a topic for another post.