The few times I’ve gone camping in my life, I found the sleeping bag uncomfortable. You’re completely covered in a sleeping bag. It’s all or nothing. You can adjust what you have on so that once you’re all zipped up in the bag, the combination of your clothes and the thick insulation provided by the bag is likely a perfect match for the cold outside. But what happens if you gradually get warmer inside the bag? You try unzipping and you fold down the flap and then… you’re freezing. It’s still cold outside. The problem is there are no layers, no way to adjust the coverage, no ‘in between’ option. It’s too late to get back out and remove some clothes. You can’t stand in the tent. You don’t want to step on someone else. That’s a workout at 2:00 am and you’ll never get back to sleep.

What about if you get into the bag in nothing but the nakedness you’re used to, and you wake up in the middle of the night shivering because the temperature has dropped off a cliff under that clear night sky you appreciated only a few hours before? You can see your breath. This is how people get sick. You have no choice; you have to get out of the bag and put some clothes on. You’re desperately groping around trying to find your clothes and coat in the dark, reaching over or worse, kneeling on a human. You worm into your pants, pull on your hoodie, snap up your coat, and zip back in. You’re lying on your back, winded from the effort. Turning to the side is difficult because of the bulk you have on and the friction of the flannel. There’s no room to even breathe now. And you’re gonna regret that coat.

The Covered Call

Nearly every article I have ever read on options spends considerable time on fundamental definitions of what options are before ever getting into the real purpose of the article. I really don’t want to spend time on that. If you’re a careful reader I think you can learn on the fly but know that if something I write isn’t clear to you, understanding can be achieved with a quick internet search.

Within the Portfolio for the Ages, there have been two opportunities to sell or write calls and I have done so. I say ‘opportunities’ because it has only been an option (pun intended) when there have been at least 100 shares in the position. This has been the case with Telephone & Data Systems Inc [TDS] and Leggett & Platt Inc [LEG]. TDS was cheap enough in the beginning and LEG eventually became cheap enough such that the position has grown to over 100 shares.

The reason I wrote the call contracts was, ultimately, as a hedge. In the case of TDS, I wanted to supplement the dividend income because I felt their financial condition was fragile and a dividend reduction was possible. In the case of LEG, their dividend reduction was more of a surprise and the sold calls are an attempt to replace that lost income while I wait for the stock price to recover somewhat. At the core of both of these situations was the idea of generating more income in exchange for giving up the possibility of capital gains beyond a certain point.

There is another significant difference in the two positions that I would like to illuminate. Unlike with LEG, in the case of TDS I do not have a perfect multiple of 100 shares. There is a certain amount of comfort in this. Let me explain.

A put or call option contract on a given stock represents 100 shares of that stock. In the case of selling one call option contract on a stock position where you already own at least 100 shares, we say that the call is ‘covered’. Why? Well, because in the event the purchaser of that call option chooses to exercise the call, which he would only do if the stock’s price has risen above the strike price of the call on or before the expiration date of the call, you got it covered. Huh? When the call is exercised by the purchaser, the seller is ‘assigned’ and obligated to sell those 100 shares to the purchaser at the strike price, i.e. for less than what they’re worth in the market. Now, if you didn’t already have those shares, you would have to first buy them in the market, at some higher price, and then instantaneously sell them for the agreed upon strike price. But if you already own them, that isn’t necessary, you just sell them upon assignment.

What’s important here is that ‘covered’ means the shares represented by the call option contract were already held, not that the entire position was necessarily ‘covered’ by calls. Get it? The calls are covered, not the shares. For instance, Royal Dividends has 345 shares of TDS and three call contracts. It was not an option to sell four covered call contracts because one needs 400 shares to do that1. Thus, there are 45 naked or uncovered shares of TDS. But that rather common terminology really isn’t accurate, is it? We already established that the term ‘covered’ applies to the calls. So here we simply have shares that ‘are not needed for covering’, but that sounds a little awkward. How about ‘free’? Nah, that makes it sound like the shares can be taken away at no cost. ‘Unassigned’? Well, all the shares are unassigned until some are assigned, so that doesn’t work either. ‘Non-callable’? That’s more of a bond term. Let’s move on.

The covered call strategy is often sought from the get-go and a buy/write trade starts the position. In other words, a person will buy the shares and write the calls in one transaction and perfectly match the calls to a perfect multiple of 100 shares. Of course, from there the decisions for strike price, expiry date, and premium all come into play.

It is sometimes the case, as with Royal Dividends and LEG, an investor may acquire more shares of a stock, rounding up to a perfect multiple of 100 shares, for the sole purpose of maxing out on the number of calls that can be written. Typically, this is done to maximize income and eventually exit the position entirely.

Writing calls is all about increasing one’s income. One can choose a lower strike price and collect a higher premium or a higher strike price and collect a lower premium. If you’re primarily a dividend investor interested in supplementing or augmenting a lower yielding dividend stock and would rather not see the shares called away2, it makes sense to choose a higher strike price. The higher strike price would allow for quite a bit of price appreciation before the stock were to be called away and if the price gets above that strike, so be it.3

But there is another, often overlooked option (aha).

A Remnant

Consider selling calls using only a portion of your position as cover. It’s another variable that provides flexibility. Perhaps you have a low volatility stock and the call premiums for higher strike prices are virtually non-existent, limiting you to lower strikes that make the eventual assignment of the shares a bit too likely or not far enough above the current price level to allow for significant capital gains. This is the perfect time to consider selling calls at a lower strike but on a fraction of your shares. Not every stock is tied to an option. (That’s it!) In other words, some shares are ‘untethered’. If the stock price heats up, this gives the stock position a chance to breathe. This is not your sleeping bag; this is comfort.

This might just be the perfect balance of the covered call strategy. Let’s look at an example using Verizon Communications Inc [VZ].

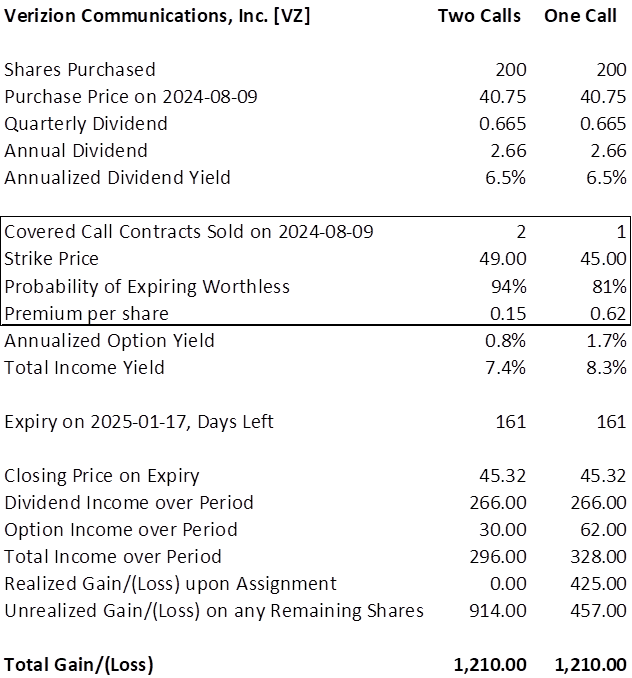

All of these numbers were grabbed from real time data on 2024-08-09. The first column represents using all 200 shares to cover two sold calls with a strike price chosen so that there is only a 6% chance the shares are called away. The premium of $0.15 is not much and if this trade were repeated every six months, the effective increase to the dividend yield would be about 80 basis points. The problem here is that the call writer has forfeited all rights to any gains that could otherwise be had in the event the stock price moves above $49.00. This is the sleeping bag situation. It’s all or nothing; all the gains up to $49.00 and nothing more thereafter.

The second column is clever. Here the investor shows some restraint. If one is willing to accept 3X the likelihood of seeing their shares called away (19%) with a lower strike of $45.00, they can receive about 4X the premium per share upfront ($0.62 vs $0.15). That 4X is interesting because now the investor can sell just one call, placing only half the shares at risk of assignment, and still receive 2X the premium in absolute dollars! A remnant of shares remains untethered, providing the investor the opportunity to share in the glory of massive appreciation should the stock price really take off.

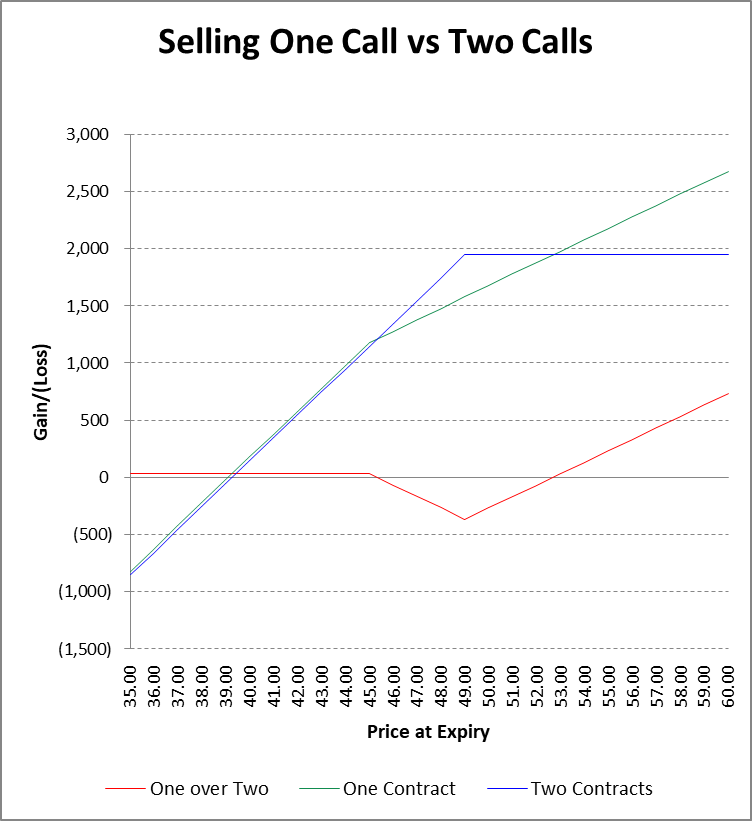

I chose a 2025-01-17 closing price of $45.32 to illustrate one of the prices where the two scenarios achieve the same level of profitability. It should make sense that it is a breakeven point since the ‘One Call’ trade has a $32 premium advantage that begins to disappear when the stock reaches the $45.00 strike and fully disappears when the price reaches $45.32. Below we take a look at the performance of these two option trades over a range of prices at close on the expiry date4.

Conclusion

The ‘Two Calls’ trade outperforms in that sweet spot between the two strike prices, reaching a maximum advantage of $368.00 over the ‘One Call’ trade at the $49.00 strike. But then the performance begins to reverse and at a price of $52.68, the two trades both produce gains of $1,946. And this is the best the ‘Two Calls’ trade can ever do. VZ could go on to $60.00, and not a dollar more profit is to be had. However, the ‘One Call’ trade has just 100 shares capped at its strike of $45.00. There is a remnant of shares, steadfast in their devotion, amidst the trials and tribulations of the times, to the promise of even greater degrees of price appreciation that most investors dare not dream of. At a price at expiry of $60.00, this trade has a gain of $2,678.

Let’s not forget that an 81% chance of expiring worthless is still relatively high. Four times out of five, the stock price won’t be above $45.00 at expiry and the investor would not suffer one iota for having chosen the lower strike in exchange for the higher premium.

Position size within a stock portfolio is very important and so understandably, it is not always feasible to possess more than 100 shares of a stock, particularly expensive ones (the investor in the example above needs $8,150 for those 200 shares of VZ, and somewhere north of a quarter of a million dollars for a position weight of perhaps 3%).

However, for certain investors of means with a desire to both increase income and still participate in significant capital gains in a given stock position, the strategy of writing less than the maximum number of calls possible has two advantages: (1) a higher option premium yield on the whole position when carefully selecting a strike price with a slightly lower (but still relatively high) probability of expiring worthless, and (2) uncapped gains for a portion of shares in the event the share price really takes off.

Lastly, the strategy of writing less than the maximum number of calls could also be a viable way to downsize or even slowly exit a position, but only at a price you decide. There is flexibility and comfort here and you can sleep at night even if things heat up.

- There is such a thing as a naked call and one needs a margin account with a special approval level to sell them. It is nothing more than selling a call option on a stock that you do not own. Let’s suppose you sold a naked call on Lumen Technologies Inc [LUMN] with a $2.00 strike price and 2024-08-16 expiry, a month ago, when it was trading at $1.00. You might have collected an embarrassingly low amount of premium for that contract, receiving perhaps $0.02 per share or $2 per contract. Then the world turns on a whim and views LUMN as this diamond-in-the-rough Ai company (I prefer abbreviating artificial intelligence this way over using the capital of ‘i’, because in too many fonts it just looks like the nickname of Albert. This is a rather long parenthetical because I was not about to be the kind of person who puts a footnote within a footnote.) and the stock shoots up to $7 in a couple of weeks, and you are assigned early. You’re out $498 per contract on what was considered a trade with virtually zero probability of going sour, let alone seeing the stock rise 600% in two weeks. You got bamboozled! Now suppose it wasn’t LUMN but W.W. Grainger Inc [GWW] trading near $1,000 per share. You’re out half a million per contract. Suffice it to say, there is near limitless downside in selling a naked call. Some folks will say the downside is unlimited, but let’s be frank, how many stocks have ever gone up infinity in a calculable amount of time?

↩︎ - You might ask why someone would even sell a call in the first place, putting their shares at risk of being assigned, if they don’t want to sell them. That is a valid question and there are valid answers, one being about prioritizing income over capital appreciation or another being about setting a strike price high enough to compensate one for having to give up the shares. But remember that risk is not certainty. There is a probability that a stock will be called away and it is balanced by the probability that the option will expire worthless and by golly I hate to be the only one that is about to say what writers of covered calls know deep down in their soul, but here goes: There is incredible joy that comes from collecting money from strangers for something that ultimately proves worthless to them. This is true especially with covered calls. You already own the stock. It’s just sitting there in an account. Perhaps there are dividends rolling in every quarter. But to know that you can sell, say a 6-month call contract, immediately collect a premium worth double the dividends you’ll collect in that time, and have an 85% chance of keeping your shares? That’s hard to pass up.

And who are these clowns that buy calls that require a stock to trade 20% higher 6-months from now, before the call is even in a breakeven position, let alone gives the holder a chance to buy the stock at a significant bargain? Fine, most put and call contracts never even come to expiry – they’re usually bought or sold ‘to close’ the position before the expiration date because the options themselves are the reason for the trades, not shares of the underlying stock. Maybe someone bought that call hoping a quick 5% move after earnings (with say, 5 months remaining) would be enough to cause the option premium to jump up, and so they sell to close that call at a significant profit of 25% or more. Their motive for buying doesn’t matter. The truth is selling covered calls for repeatable premium has proven effective at increasing income while providing some downside protection in a portfolio.

↩︎ - There are options strategies that can be deployed in an effort to not see one’s shares called away. Each strategy requires purchasing to close the existing call and selling to open another call prior to the expiration of the original call. The key is timing. I won’t go into detail here but will list them for the interested reader:

(1) rolling out – the net effect is to keep the strike price the same, but push out the expiration

(2) rolling up and out – this increases the strike price AND pushes out the expiration

The first trade will result in an additional premium credit. The second may result in more premium if done at an optimal time, but more often than not, will carry a cost.

↩︎ - I have chosen to ignore the possibility of early assignment for the sake of keeping things simple. Even though one can exercise an American option prior to the expiration date, it is uncommon.

I also did not want to be the kind of person who footnotes a title and so this comment is for the truly dedicated. The rather awkward title is a nod to Jerry Seinfeld’s less famous show. ↩︎