On April 7, 2003, the Syracuse Orangemen defeated the favored Kansas Jayhawks 81-78 to claim the Division I Men’s College Basketball championship. Certainly, future NBA Hall of Famer Carmelo Anthony, did his part putting up 20 points and collecting 10 rebounds, but it was the freshman Gerry McNamara that made the difference for SU that day. He hit 6 of 8 three pointers in the first half putting Syracuse up 53-42 at the break. Kansas played catch-up the rest of the game and couldn’t quite get there. Of course, making only 12 of 30 free throws is a surefire way to lose most ball games, let alone a championship against a talented team.

How unlikely was G-Mac’s first half performance? Well, it stands as the record for threes made in a half of a championship game. G-Mac was able to hit 6 or more threes in a game a total of 9 times in 135 games. I do not believe he ever hit 6 in a single half before or after the game against Kansas. So that’s once in 270 halves. In fact, the odds of making exactly 6 of 8 threes for a player whose ultimate success rate turned out to be 400 of 1,131 (35.4%) is 2.3%. That means if you turned G-Mac loose into 135 games and he took exactly 8 threes in every half, you’d expect him to hit 6 in a half a total of 6 times.

That first half was unlikely.

Repeat Performance?

Now, send yourself back in time. You’ve grabbed a bag of Doritos and you’re back on the sofa during half-time of that game. Do you expect a repeat performance from G-Mac in the second half? You certainly shouldn’t. You should have at least some idea, from the announcers talking about a record just having been set or from having a basic understanding of shooting percentages, that what you just observed was highly unlikely. Not only that, a basketball game isn’t exactly a controlled experiment. Coach Roy Williams is undoubtedly livid with his defense and will be making adjustments.

Gerry McNamara scored 18 points in the first half but didn’t score in the second half. He got off two threes but they didn’t fall.

He reverted to the mean.

Well, he certainly began to. Had he missed 9 threes in the second half, we would have had a complete reversion or regression to the mean (he’d have been 6-17 and right on the average for his career). I suspect if he’d gotten off 9 threes in that second half, Roy Williams would have had a stroke.

Let’s put this concept in a cleaner mathematical context.

Flipping Coins

If you flip a coin four times and heads comes up all four times, what are the odds that the fifth coin flip comes up heads? Well, assuming that the coin is true and balanced appropriately, every coin flip has a 50% chance of coming up heads, regardless of the results of any previous flips.

If after 100 coin tosses, heads has come up 56 times, it is natural and correct to expect the proportion of heads to drop and approach 50% with more tosses. We expect it to revert to the mean. It doesn’t mean (no pun) that the probability of getting heads of any one coin toss has changed, only that as the number of tosses increases, the observed number of heads will approach the theoretical mean, which is 50% heads. If you’re wondering whether you can flip a Bitcoin, we’re done here.

Here is the definition provided by Wikipedia: In statistics, regression toward the mean (also called reversion to the mean, and reversion to mediocrity) is a concept that refers to the fact that if one sample of a random variable is extreme, the next sampling of the same random variable is likely to be closer to its mean.

I really do like the term ‘reversion to mediocrity’.

So, this is a statistical term and applies to random variables. But as we’ve already seen, if one relaxes the statistical context a bit, one can see it applies to other areas of life. Sports. Weather. Gambling. Stock Markets.

Mean Reversion in Investing

Investopedia defines it thusly:

Mean reversion, or reversion to the mean, is a theory used in finance that suggests that asset price volatility and historical returns eventually will revert to the long-run mean or average level of the entire dataset. This mean level can appear in several contexts such as economic growth, the volatility of a stock, a stock’s price-to-earnings ratio (P/E ratio), or the average return of an industry.

If you spend time looking at stock price charts you’ll observe mean reversion all the time. Just take a look at post-pandemic Foot Locker [FL]:

Guess what? I think Foot Locker is undervalued right now, but I’m not interested in buying them, because they suspended their dividend during the pandemic and frankly, that decision was rash; their dividend was well-covered at the time. They skipped one quarter and then reinstated their dividend at 25% of its previous amount. Two years later, they’re right back to the dividend they were paying before it was suspended. Oh well.

There are many, many stock and option trading strategies that are centered around reversion to the mean. I say trading and not investing. Royal Dividends is much more interested in buying and holding great businesses. We’re investing in these businesses, and we use reversion to the mean in one important way.

Using Historical P/E Ratios to your Advantage

It is unrealistic to expect a company’s earnings to climb exponentially or even linearly ad infinitum. Blame the vicissitudes of doing business in an ever-changing world. Earnings fluctuate and stock prices much more so. If we’re interested in acquiring a great company at a good price, we can look to the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E ratio). Specifically, we can compare the current P/E ratio to the same company’s historical P/E ratio.

An Example

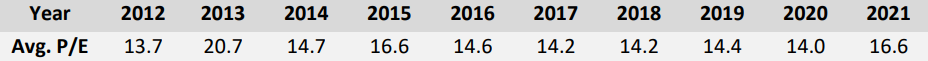

I’m a subscriber to Sure Dividend, and they have this rather convenient display for hundreds of dividend paying companies. Below is the 10-year history for Dividend King, Target Corporation [TGT]:

One thing you’ll notice is that there is a fairly narrow range, 13.7 to 20.7 and those extremes were nine and ten years ago. Trust me, the history for some stocks is all over the place, and in those cases, the average has a lot less meaning. But for Target, the 10-year average is 15.37 and is a good representation for most of the years in the decade. This means, the market is typically interested in paying $15.37 for every dollar of earnings.

Trading at $168 as of this writing, their P/E ratio is 13.7. That’s right at the low end of their historical range. In fact, just a few weeks ago, after a disappointing earnings announcement, Target dropped 25% in a day. It continued to drop for days, all the way down to $137.16, a P/E ratio of around 11.4. That was disrespectful to a Dividend King, ridiculous market behavior. Had Royal Dividends started before that, you can have no doubt I would have acquired Target after that plummet.

Even now, they’re attractively priced with 12% upside to their historical average P/E ratio. That’s at least one indication that paying $168 for TGT isn’t too much. We expect upward reversion to the mean and this would mean (pun?) 12% of capital appreciation over however long that takes. It could work the other way too. If TGT were priced over $200, the P/E ratio would be at least 8% over the average and perhaps not a great time to get in, because invariably, reversion means (yes pun) there is more downside risk than upside potential at the same earnings level.