In part one of this post, I will reveal what I consider to be a very simple formula for a wonderfully balanced soap, and I will show you how you can save some money through an easily achieved economy of scale. If, that is, you’re willing to make it yourself. If you’re at all convinced or interested, then I encourage you to read part two. Part two will not be a thorough treatment on the process of making soap, or the chemistry behind it, but I will provide enough details of how to safely make a batch of soap.

For the love of God, please don’t attempt to make soap until you understand the risk involved.

Most of the ‘soap’ that we find on the shelves today is mass-produced detergent. Real soap has naturally occurring glycerin as a byproduct of the chemistry that goes into making it. Who cares about glycerin you ask? Well, British rock band Bush for starters. Glycerin is a humectant. It helps your skin retain its own moisture, making it feel soft. The point: there is a lot of garbage in cheap mass-produced soaps, and some don’t have glycerin. Real soap is a superior product and it is possible to make it at home.

I have made dozens of batches of premium quality soap for a fraction of what they’d cost at your local Whole Foods. How? Well, now that’s the first sensible question you’ve asked.

In its purest form, soap is made up of oil (or fat) and lye. Lye is sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and water. Sometimes people use ‘lye’ interchangeably with ‘sodium hydroxide’; I prefer to use ‘lye’ for the solution of sodium hydroxide dissolved in water.

You can scour the internet and find tons of soap recipes. However, the one I present below is about the most efficient way to satisfactorily meet all of the industry-recognized characteristics of a high-quality soap.

Formula

I prefer the term formula over recipe, because this isn’t food. Plus, I love chemistry projects.

Okay, so soap isn’t food, but soap is a bit like coffee. A single origin roast will accent some notes at the expense of others, whereas a blend of different roasted coffee beans can be used to achieve a more balanced cup. Similarly, one can make a soap from a single oil, but doing so will produce a bar that inevitably falls out of the acceptable range of one or more desirable characteristics (see below). And just as a single origin roast may be someone’s favorite coffee, a soap made from just olive oil or just coconut oil may be exactly what the user wants. Some people like a harder bar with less lather, and others want creamy suds abound.

Here is my simple formula for a nice bar of soap:

| 50% | Olive Oil | Olea Europaea (Olive) Fruit Oil |

| 25% | Palm Oil | Elaeis Guineensis (Palm) Oil |

| 25% | Coconut Oil, 76 deg | Cocos Nucifera (Coconut) Oil |

Does not the use of Latin really get the scientific mind humming? I will provide the exact amount of lye in a moment, but this blend of three oils produces the following fatty acid profile:

| Fatty Acid | % |

| Lauric [12:0] | 12 |

| Myristic [14:0] | 6 |

| Palmitic [16:0] | 20 |

| Stearic [18:0] | 3 |

| Ricinoleic [18:1 – OH] | 0 |

| Oleic [18:1] | 47 |

| Linoleic [18:2] | 9 |

| Linolenic [18:3] | 1 |

Now, if you’re thinking the largest percentage belonging to oleic acid has something to do with the double portion of olive oil, you would not be mistaken. Ditto if you noticed that palmitic acid seems like it might have something to do with palm oil. Perhaps you noticed that the percentages don’t add to 100%. That’s because some oils are not comprised solely of these fatty acids, and these fatty acids are listed for their relevance to soap. But if you noticed that though I referred to this soap as ‘balanced’, but that it has very little of some fatty acids and zero ricinoleic acid1, calm down. Balanced refers to the qualities that this soap possesses, a direct result of its fatty acid profile, not the fatty acid percentages themselves.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Hardness [29 – 54] | 40 |

| Cleansing [12 – 22] | 18 |

| Conditioning [44 – 69] | 56 |

| Bubbly [14 – 46] | 18 |

| Creamy [16 – 48] | 23 |

| Iodine [41 – 70] | 58 |

| INS [136 – 165] | 153 |

This soap is not a bush-league, cheap-ass olive oil soap serving as a glorified delivery mechanism for a wonderful, yet fleeting scent of lavender you get at the local flea market. This soap cleans, conditions, lathers. It doesn’t turn to mush as it gets used. It can be used as a shampoo bar (for those with shorter hair) and there’s enough staying power to the lather to provide a decent shave for the legs or the face, whatever your pronoun and desire.

The Iodine and INS scores are not as intuitive; they are just additional measures of the hardness of a bar. With Iodine, it is the lower the number, the harder the bar. With INS, it is the higher the number, the harder the bar. Suffice it to say, the soap produced by this formula is sufficiently hard, largely because of the palm oil.

Shopping List

Here are the links to the absolute cheapest, yet practically-sized containers available to make one batch of 10 bars of soap. These are the items you likely do not have already. The list does not include the other things that most people have handy such as a wooden spoon, stock pot, etc.

- Sodium Hydroxide (1 lb)

- Distilled Water (1 gal)

- Coconut Oil (15 fl oz)

- Palm Oil (16 fl oz)

- Olive Oil (16 fl oz)

- 42 oz Flexible Rectangular Soap Mold in Wooden Box (1)

Though it is possible to buy distilled water online, it makes more sense to grab a gallon at the grocery store. It may also be cheaper to acquire coconut oil and olive oil at the grocery store too. Palm oil and sodium hydroxide are harder finds.

Make sure the sodium hydroxide is food grade, as it will be the purest available. Distilled water is better for soap, because minerals or chemicals present in other sources of water may react with the lye and eventually alter the look of the soap down the road. The coconut oil should be the kind that will become liquid at 76 degrees and higher. Like coconut oil, both palm oil and palm kernel oil are solid at room temperature. Don’t buy palm kernel oil for this soap formula. Lastly, since you’re not going to eat this soap, you don’t need extra virgin olive oil, just olive oil or olive oil (pomace). Do make sure it is 100% olive oil.

A quick comment on the slab-style soap mold. There are many pre-shaped soap molds with 10 or 12 rectangular or other-shaped cavities, which promise perfectly shaped bars. However, quite often time is of the essence during the final stage of pouring the raw soap into a mold. It is far easier to pour into one, large mold and cut the soap into bars with a knife later. Silicon baking molds are absolutely fantastic, and the perfectly sized wooden box keeps the silicon mold’s shape rigid until the raw soap solidifies. Trust me, until one becomes a seasoned soap maker, this product is the easiest to use.

The Details

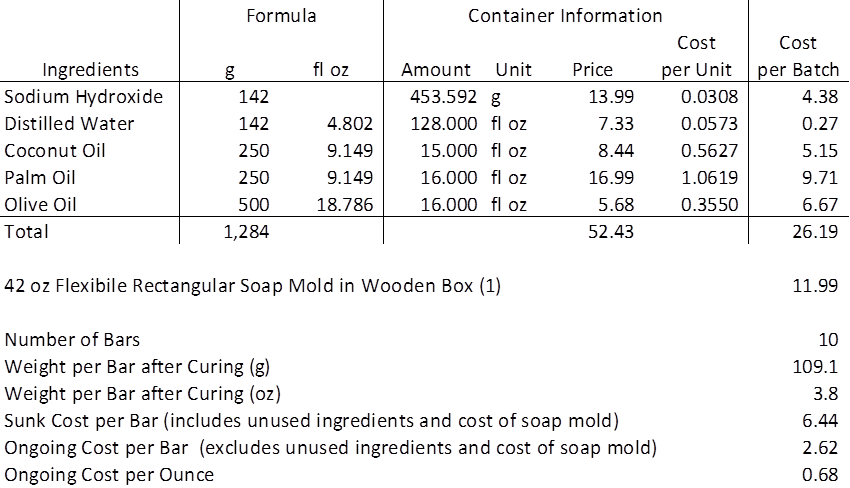

Below I lay out the exact amounts of each ingredient needed, the smallest/cheapest container practically available in order to make one batch, and the costs per unit and per batch. Multiple units are provided because costs are more easily compared in certain units, while weight-based units such as grams are critical for actually making the soap.

Sunk cost assumes that everything was purchased to make this one batch and only this batch and that any excess ingredients and the silicon mold are thrown out and not even used for culinary purposes. Una vergogna!

Ongoing costs assume that you keep buying these containers as needed to make more batches; the soap mold is only purchased once so it is excluded from this cost. The prices in the tables that follow all match the links provided as of the date of the publication of this post.

The amounts of sodium hydroxide and water are shown in the table. There is an exact amount of lye required to completely saponify any particular blend of oils. One can use a free online soap calculator to determine this amount. However, because oils are extracted from nature and not made in a lab, their true saponification numbers are more readily described by a range of values rather than a point estimate. An excessive amount of lye in the soap will burn the skin. To avoid pairing too much lye with the oils it is meant to saponify, I have applied a 4.5% discount2, to the theoretically exact number needed. Think of it as a 4.5% margin of safety (this is an investment website afterall). Using only 95% of the theoretically exact number means there is almost no chance the soap will be ‘lye-heavy’.

What about the cost of this batch? Certainly, a sunk cost of $6.44 per bar is not a cost savings. Things get more interesting if you continue making batches of soap. The cost of $2.62 for a quality soap starts to make more sense, though one could argue that if there is savings, it isn’t quite worth the effort.

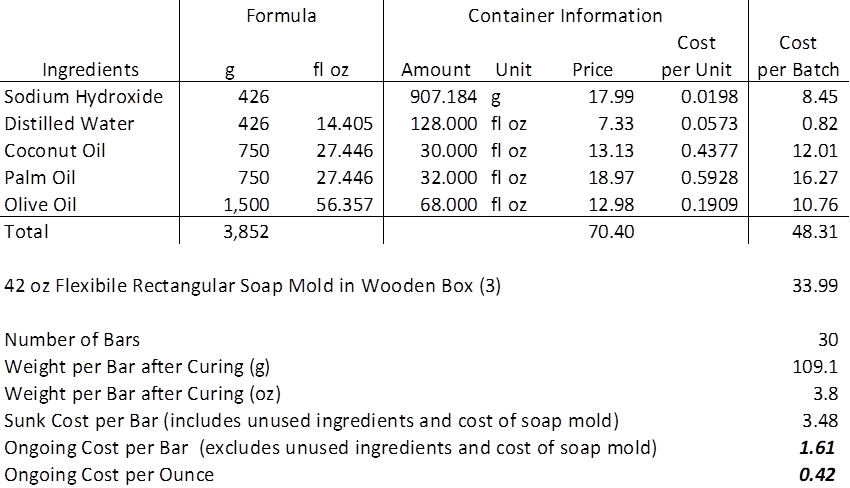

Scaling Up

There is an advantage to purchasing more at one time. If you’re willing to shell out just $18 more, you’ll have enough product to make 30 bars of soap for your first batch. Here are the amounts and their updated links:

- Sodium Hydroxide (2 lbs)

- Distilled Water (1 gal)

- Coconut Oil (30 fl oz)

- Palm Oil (32 fl oz)

- Olive Oil (68 fl oz)

- 42 oz Flexible Rectangular Soap Mold in Wooden Box (3)

A gallon of water is still plenty and so there is no money saved there. However, note just how much the cost per unit drops off for everything else by acquiring twice as much (with the exception of the olive oil, which is 4X). Technically, a second pound of sodium hydroxide is unnecessary but the drop in cost per unit is worth it should one embark on making additional batches.

Save on Savon

It really isn’t possible to save money over the cheapest bars of soap available in the marketplace. A person working at home in the kitchen simply can’t compete against a conglomerate. But if you’ve been buying decent, premium bars, you definitely have a shot.

The second table of financial results shows the cost per ounce of soap has dropped considerably and is well under what most commercially available premium soaps cost3. Now, if you also use this soap in place of liquid hand soap4, shampoo, and shaving cream, the savings really add up. Liquid soap is relatively cheap on a per ounce basis, but one dispenses more liquid soap to wash their hands than what is consumed using a hard bar. Scaling up yet again would certainly bring further reductions to unit cost and the batches could be bigger. And since one person does not need so much soap, perhaps selling bars on the side becomes an option.

I should mention that it is very tempting to add fragrance and dyes to homemade soap. If you’re goal is saving money, this is where you’re likely to fail. Be careful with these extras. If you go this route, use only natural, high-quality dyes appropriate for soapmaking and pure essential oils for fragrance. Even if you don’t want to be in the business of selling soaps, these enhanced soaps make great gifts.

1Only one oil provides ricinoleic acid, castor bean oil. A little of this oil goes a long way and imparts a wonderful lather in a soap. However, it is relatively expensive and not the only way one can achieve a soap with a nice lather.

2Sometimes this discounting process is called superfatting – providing an amount of oil beyond that which will react with the lye provided. Same effect, different perspective.

3The bar weights and the cost per ounce reflect the process of curing the soap. Once the saponification process is complete, the bars need to cure for a few weeks and in this time the soap will lose perhaps 10-15% of its weight in the form of moisture. I have assumed 15% to be conservative in the cost per ounce figures. This allows for better comparisons to soaps you can purchase at a store or online, which have likely lost all their moisture already.

4There is a process for making liquid hand soap that involves not sodium hydroxide (NaOH), but potassium hydroxide (KOH). If you have a tried-and-true formula and process, please share!